Beyond Spaghetti Code: Measuring Your Progress (Part 3)

Six years ago, Jim Kring wrote about how a simple LabVIEW VI can turn into a tangled mess and how to avoid it. These posts are some of our most popular and have resulted in very interesting email conversations from LabVIEW users who say "this is exactly what happened to me."

But there's one question that keeps coming up that is not addressed in these previous articles:

"How do I know if I'm actually making progress?"

You have read about cluster type definitions, state machines, comments... but when you're knee-deep in a real project with real deadlines, how do you know if your code is getting better or if you're just putting lipstick on a pig?

The Problem with "Best Practices"

Here's the thing about best practices: they're easy to nod along with and hard to actually verify.

"Keep your block diagrams to one screen." Great. But what about that one VI that's almost too big? Is it a problem or is it fine? I can't count how many times I've seen a block diagram that's technically one screen (on a 4K monitor in full-screen mode...).

"Use subVIs for reusable code." Sure. But how much duplication is too much? When does copy-paste become a maintainability issue?

"Document your code." Okay, but what counts as "documented"? A few comments? VI descriptions? A README?

When it's just you writing code, you can kind of feel your way through these questions. However, the moment you're working on a team, or you inherit someone else's code, or you come back to your own code six months later, you need something more concrete than "I'll know it when I see it."

What We Actually Check

At JKI, we've worked on many LabVIEW projects over the last 25 years. Some were started from scratch and many were inherited codebases that had grown out of control. Over time, we started to standardize what we look for when evaluating code quality.

However, whether you're building a prototype, a production test system, or a customer-facing application, one constant is guaranteed: your code will change (requirements shift, features get added, people leave teams, etc). The question isn't whether your code will need to adapt; it's whether it can. That's what this checklist helps you evaluate.

So what's on the list?

22 items across five categories:

Architecture: Can your code grow without growing pains? Compact block diagrams and separation between UI, logic, and hardware mean new features don't require untangling old ones.

Code Reuse: Can you find what you need? Clear naming, organized libraries, and no duplicate code mean less time searching and fewer places for bugs to hide.

Data Management: Is your data working for you or against you? Clusters, type definitions, and wires (not variables) prevent the race conditions and mysterious bugs that kill debugging time.

Documentation: Will this code make sense in six months? VI descriptions and comments that explain why (not just what) save hours of reverse-engineering.

Maintainability: Can someone else make changes (ex: fix a bug) without breaking something else? Consistent error handling and tracked technical debt mean changes don't cause surprises.

Each item gives you something specific to assess - no hand-waving required. Add them all up and you get a score out of 22.

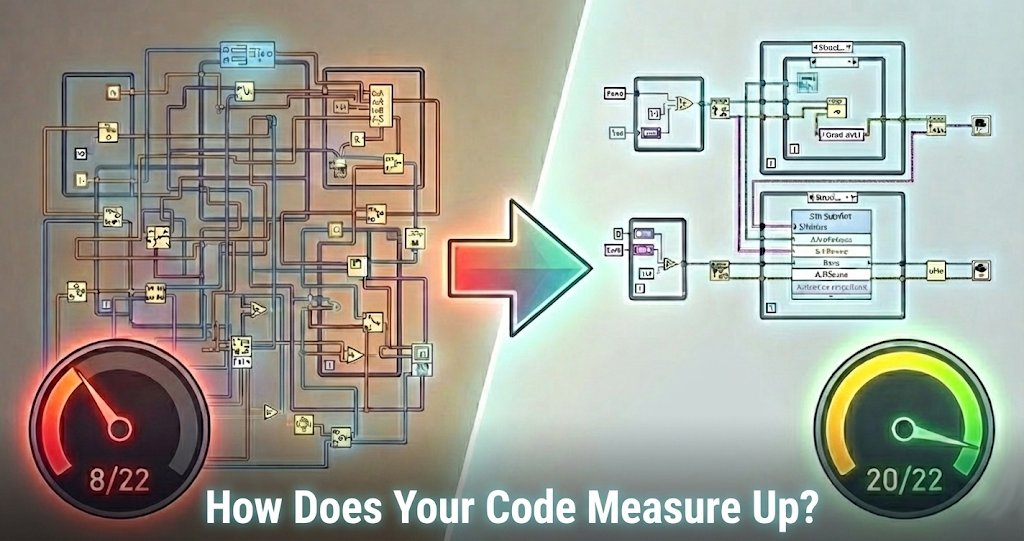

How Does Your Code Measure Up?

Score your codebase against the 22-point checklist JKI engineers use on professional projects. Covers architecture, code reuse, data management, documentation, and maintainability.

Get the Free Checklist →What Your Score Tells You

The scoring bands are pretty straightforward:

- 20-22: Production ready. Your code is solid.

- 15-19: Good foundation. Address the gaps before you scale.

- 9-14: Needs attention. Prioritize architecture and maintainability.

- 0-8: High risk. Consider refactoring or getting expert help.

These checks are not intended to be an in-depth diagnostic of a specific codebase but more of a "health checkup." It's not a pass/fail test either. A score of 14 doesn't mean your code is bad. It means you have an idea of where to focus your improvement efforts.

I've also found it useful for teams to score the same codebase independently and then compare notes. The disagreements are usually more valuable than the agreements. They surface assumptions about what "good code" means that people didn't even know they had.

Get the Checklist

We've packaged this into a one-page PDF you can use to audit your own codebase. It takes a few minutes to go through, and you'll come out with a clear picture of where you stand.

Get the Free Code Quality Checklist

Score your codebase in a few minutes across architecture, code reuse, data management, documentation, and maintainability. The same checklist JKI engineers use on professional projects.

Download the Checklist →Missed Parts 1 and 2?

If you haven't read the earlier posts in this series, they're still worth your time:

- → Part 1: A Recipe for Spaghetti Code in LabVIEW - How a simple VI turns into a tangled mess

- → Part 2: Avoiding Spaghetti Code in LabVIEW - 3 steps to avoiding the problem (plus the template we use)

Have questions or feedback on the checklist? Leave a comment below or message me on LinkedIn.

Enjoyed the article? Leave us a comment